-

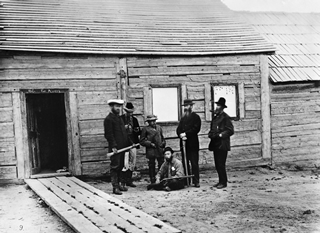

The first oil well in North American is drilled.

The first oil well in North American is drilled in Lambton County, Ontario, in 1857/58. Although the oil field here is relatively small and nearly exhausted after a few years of production, it marks the beginning of Canada’s oil industry. The region, particularly around Sarnia, continues to be a major centre for petrochemical research and refinery operations.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-302-9

-

Oil seeps in southern Alberta are documented.

George Mercer Dawson conducts numerous surveys of western Canada and its resources for the International Boundary Commission (1873-1874) and the Geological Survey of Canada (1875-1901). In 1874, he reports oil seeps in the Waterton area, 225 km (140 mi.) south of Calgary.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-302-7

-

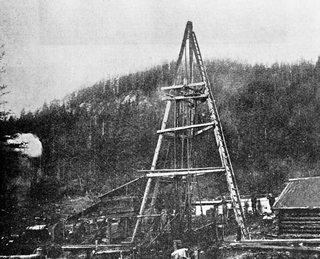

The first producing oil well in Western Canada is drilled.

In 1902, the Rocky Mountain Development Company drills a well on Cameron Creek (in what is now Waterton Lakes National Park). It is the first producing oil well in western Canada.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-1585-7

-

Petroleum is found in Alberta’s Turner Valley.

On May 14, 1914, the Dingman No. 1 well strikes wet gas in the Devonian reef formation deep under the surface of Turner Valley, Alberta. Other wells are soon drilled, and the Turner Valley field becomes Canada’s largest oil and gas producer.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, P1304

-

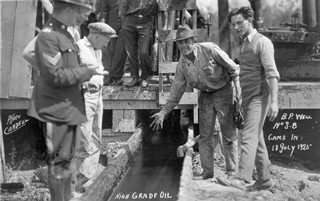

A new discovery rekindles hope that large reservoirs of oil will be found beneath Alberta.

Discovered by British Petroleum in 1923, the large Wainwright oil field revives hopes for the Alberta oil industry.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A10793

-

Control of natural resources is transferred to the provincial government.

The agreement transferring jurisdiction of natural resources from the federal to the provincial government is signed in Ottawa, December 14, 1929, and enacted the following year. (Seated, starting second from left, are Hon. Charles Stewart, Minister of the Interior and Mines; Rt. Hon. W. L. Mackenzie King, Prime Minster of Canada; and Hon. John Brownlee, Premier of Alberta.) The transfer allows Alberta to realize the full economic potential of the oil and gas resources found within its borders.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A1092

-

The Oil Column phase of Turner Valley development begins.

The Royalties No. 1 oil discovery, in the Mississippian geological structure under Turner Valley, sets off another oil boom for the region.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-2335-2

-

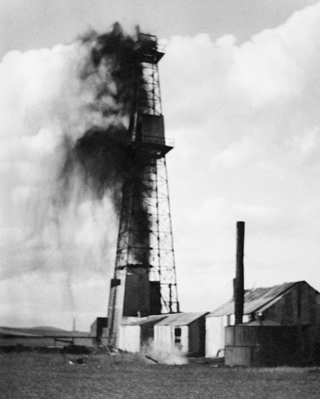

Leduc No. 1 sets off the modern oil sector in Alberta.

Imperial Leduc No. 1 blows in, setting off the modern oil sector in Alberta. The discovery of the Leduc oil field, then the largest and most lucrative yet found, comes after decades of fruitless searching and drilling. It marks the beginning of Alberta’s modern oil industry and completely revolutionizes the province’s economy and prospects.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, P1342

-

Additional oil discoveries confirm Alberta as a major oil producer.

Oil derricks dot the landscape, and smoke from a new oil well rises from the horizon beyond the hamlet of Redwater. On the heels of the Leduc discovery, Imperial Oil finds a second major oil field near Redwater, northeast of Edmonton. Larger and easier to access than Leduc, this discovery confirms Alberta’s future as a major oil producer.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A9763

-

The Interprovincial Pipeline expands the market for Alberta’s oil.

Completed between Edmonton, Alberta, and Superior, Wisconsin, in 1950, the Interprovincial Pipeline is a vital transportation link that makes Alberta’s oilfields financially viable. By 1956, the pipeline is expanded and extended to Sarnia, Ontario, and is transporting more than 200,000 barrels a day.

Source: Julian Biggs/National Film Board of Canada/Library and Archives Canada/PA-122742

-

Alberta’s oil production is connected to Pacific markets.

The Trans Mountain Pipeline, completed from Edmonton, Alberta, to Burnaby, British Columbia, in 1953, opens up Pacific markets for Alberta’s oil production.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A8495

-

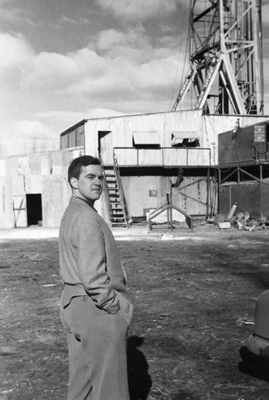

“Fracking” opens up previously inaccessible oil reservoirs.

A wellsite geologist stands in front of the Pembina No. 1 oil well. A joint venture of two oil companies, this well successfully strikes oil about 100 km (62 mi.) southwest of Edmonton. The oil at Pembina is accessed by a developing technology called sandstone fracturing or “fracking.” This technology makes it possible to extract previously inaccessible oil reserves and becomes more widely used throughout Alberta in the following decades.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-5103-9

-

Oil is discovered in Alberta’s remote northwest.

In 1965, the Banff Oil Company drills successful wells in this region. They are the first major oil discoveries in this remote area of Alberta’s northwest.

Source: Glenbow Archives, S-236-46

-

The OPEC oil embargo rocks energy markets.

Starting in 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) begins restricting oil exports to much of the Western world, including Canada. Fuel shortages become common, and the price of Alberta oil, one of the few remaining reliable and friendly sources of oil for industrialized nations, skyrockets.

Source: Library of Congress, LC-U9-37734-16A

-

West Pembina injects new life into Alberta’s oil sector.

In October 1977, Chevron Oil opens the West Pembina oil field. It is the largest discovery in ten years and revives hopes for Alberta’s oil sector, which had been suffering from a lack of new discoveries over the previous decade.

Source: WikiCommons/Qyd

-

The NEP alienates Alberta’s oil patch.

The National Energy Program is created by the federal government in 1980 to ensure a reliable and affordable supply of oil and gas for Canadian industry. The provincial government perceives it as an unwarranted intrusion into its affairs and as sacrificing Alberta’s interests in favour of those of Central Canada. Although a compromise is reached in 1981, bitter memories of the NEP continue to characterize Alberta-Central Canada relations.

Source: CP Photo/Dave Bunston, 03263367

-

The Western Accord brings NEP regulation to an end.

Within a year of this meeting, the Governments of Alberta, British Columbia and Saskatchewan will negotiate the Western Accord, which ends the National Energy Program, deregulates oil prices and encourages new investment in western Canada’s oil sector.

Source: CP Photo/Pat Price, 673836

-

Environmental concerns challenge the practices

of the petroleum industry

Images such as these feed concerns through the Western world about environmental damage due to industrial development. In 1987, the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development releases the report Our Common Future. It encourages the concept of “sustainable development” in an attempt to balance First World concerns about human rights and environmental degradation with Third World nations’ need for economic development. Although not directly related to the oil sector, this concept forms the basis for future anti-pollution and climate change strategies.

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-2864-20312

-

The World Petroleum Congress meets in Calgary.

The World Petroleum Congress, held for the first time in Canada, attracts industry and political leaders from around the world. A parallel counter-congress and protests occur in the city at the same time. As the new millennium approaches, Alberta’s oil sector faces pressure from increasingly dedicated and organized environmental and human rights activists.

Source: CP Photo/Adrian Wyld

-

The oil sands dominate oil production in Alberta.

In 2002, conventional oil production in Alberta is surpassed by oil sands production for the first time - a sign of the changing focus of Alberta’s oil sector.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, GR1989.0516.394#3