-

Alberta’s first natural gas discovery in Langevin eventually leads to the designation of Medicine Hat as the “Gas Town of the West.”

Gas Town of the West

Source: Image courtesy of Peel’s Prairie Provinces, a digital initiative of the University of Alberta, PC010811

-

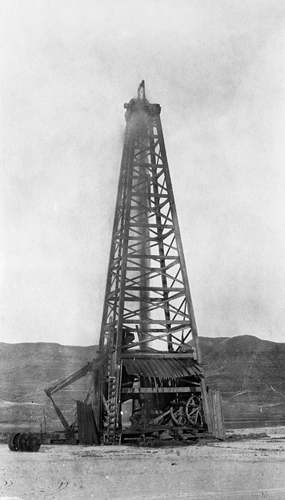

At Bow Island, Alberta, the largest gas well drilled in Canada to date is directed by Eugene Coste, the “father of the natural gas industry.”

Gas well blowing at Bow Island, Alberta

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-4048-4

-

Eugene Coste builds a 270-km (168-mi.) long pipeline, one of the longest and largest pipelines at that time, to carry Bow Island gas to Calgary and Lethbridge.

Pipe for gas line, Bow Island area, Alberta, 1913

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-4048-1

-

Natural gas wet with condensate is first discovered in the Cretaceous level at Turner Valley with the Dingman No. 1 well by Calgary Petroleum Products, the company originally founded by William Stewart Herron.

Turner Valley Discovery Well Blowing, 1914

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, P1883

-

Edmonton finds a natural gas supply in Viking, Alberta, but delays development due to war-related anxieties.

Edmonton Gas Well, Viking, Alberta, ca. 1914

Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-1328-66092

-

.jpg)

Royalite Oil Company Ltd., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Imperial Oil, gains entry to Turner Valley and begins an aggressive campaign to dominate petroleum production there.

Original Royalite absorption, compression and scrubbing plant, ca. 1926

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, P1882

-

Edmonton, Alberta, receives its first delivery of natural gas from the Viking-Kinsella field that had been discovered in 1914.

Pipeline at MacDougall Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta, 1923

Source: Glenbow Archives, ND-3-2062

-

Royalite Oil punctures the gas condensate reservoir in the Mississippian rock formation at Turner Valley, and Royalite No. 4 erupts in fire.

Burning Gas at Royalite No. 4, Hell’s Half Acre, Turner Valley, Alberta, 1924

Source: Glenbow Archives, ND-8-430

-

The Canadian federal government transfers control of natural gas and other natural resources to the provincial Government of Alberta through the Natural Resources Transfer Acts of 1930.

In December 1929, Mackenzie King signs natural resources transfer agreement prior to the passage of legislation in 1930.

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A10924

-

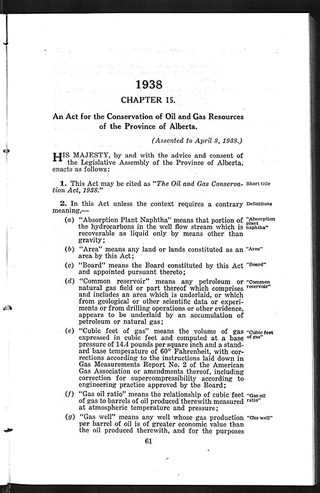

Oil and Gas Resources Conservation Act becomes law, and the Petroleum and Natural Gas Conservation Board, now the Energy Utilities Board, is formed as the regulatory authority for all gas and oil operations.

An Act for the Conservation of the Oil and Gas Resources of the Province of Alberta

Source: The Oil and Gas Conservation Act, SA 1938, c. 15

-

The largest gas reservoir in Canada at the time of discovery, the Jumping Pound field becomes a symbol of the need to resolve the stalemate over whether or not Alberta should export its natural gas; without adequate markets, it remains shut in until 1951.

Shell Oil Jumping Pound Gas plant, 1952

Source Provincial Archives of Alberta, P3009

-

.jpg)

Efforts to promote natural gas as a safe, clean alternative to coal help the market expand rapidly, and large-scale processing and pipeline projects are constructed to serve the growing market.

But of course! Gas The Modern Fuel! In the years following World War II, the development and use of natural gas skyrockets due, in part, to rigorous marketing.

Source: City of Edmonton Archives, EA-275-1776

-

In 1952, facilities in both Turner Valley and Jumping Pound begin to convert the toxic hydrogen sulfide in sour gas into benign elemental sulfur, and by the 1970s Canada becomes the largest exporter of sulfur in the world.

Handling sulfur at Madison natural gas facility, Turner Valley, 1952

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, P2973

-

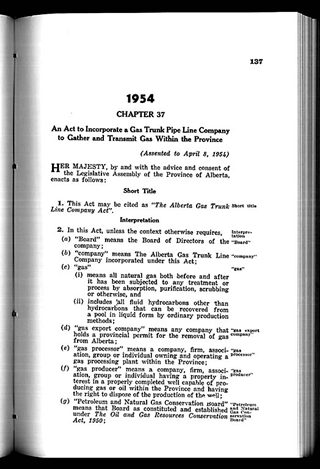

Alberta Trunk Line Company is established in order to gather and transmit Alberta’s natural gas for domestic consumption as well as for export outside of the province.

An Act to Incorporate a Gas Trunk Pipe Line Company to Gather and Transmit Gas within the Province

Source: The Alberta Gas Trunk Line Company Act, SA 1954, c. 37

-

TransCanada Pipeline exports the first gas piped to eastern Canada over a single pipeline, longer than any other single length of pipeline in North America at that time.

TransCanada Pipeline

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, P1355

-

.jpg)

Tom Adams and Stan Jones found the Meota Gas Co-operative, the first in what becomes a widespread movement to provide gas service throughout Alberta’s rural areas.

Tom Adams (l) and Stan Jones (r)

Source: Courtesy of Gwen Blatz

-

Prime Minister Trudeau introduces the national Energy Program (NEP), which sets prices for oil and gas well below international prices.

“Just relax...we’re just going to take a sample.” November 14, 1980

Source: Glenbow Archives, M-8000-710

-

The Lodgepole sour gas blowout smells up the air for weeks, highlighting a growing conflict between the desire for economic development and the need to safeguard the public.

Amoco sour gas blowout at Lodgepole near Drayton Valley, 1982

Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta, J3747-1

-

As conventional sources of natural gas have matured and declined, the industry has increasingly focused its efforts on developing unconventional gas resources such as shale gas, tight gas and coal bed methane.

Tied in coal bed methane (CBM) well, Ponoka, Alberta

Source: Courtesy of Encana Corporation